Would we have an LNP government now if we used the NZ provisional voting system?

If you look back at the last thirty Australian Federal Elections, the Australian Labor and Liberal National Parties have won the countrywide two-party preferred vote exactly fifteen times each. If our electoral system were accurately translating Australian voters’ wishes into election outcomes – as Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said in February that it should – then this would mean that the ALP would have been in government just as often as the LNP. But they haven’t. In fact, the LNP has been in government nearly twice as often as Labor (nineteen times to Labor’s eleven).

Great news for LNP supporters – not so much for everyone else.

How should a voting system work?

According to Malcolm Turnbull:

These were the words Turnbull used to justify changes made to the Senate voting structure in February this year – citing Ricky Muir’s election to the Senate with less than 1% of the primary vote as justification that the current Senate voting system was broken.

Turnbull is right – to the extent that the goal of an electoral system in any democracy should be to create a parliament that represents the wishes and voices of its citizens. Unfortunately, Turnbull’s actions didn’t entirely reflect the sentiment he expressed. If they had, then his focus would have been firstly on reforming the voting system we use for the House of Representatives. Why? Because the voting system used to elect politicians to our House of Reps was – and remains – far less representative of Australian voters’ wishes than the one utilised for the Senate.

What’s wrong with the voting system used for Australia’s House of Representatives?

In determining whether any voting system accurately represents the wishes of its voters, you need to look at who or what it is that needs to be represented. When it comes to elections, the two most important ways citizens of a democracy typically expect to be represented are:

- By location – we want people who can speak to the issues that are relevant to where we live; and

- By political perspective (or party) – we also want a say in the policies our government implements and who gets to govern the country.

The main problem with the voting system we currently use in our House of Representatives is that it is outdated. Unlike other more modern systems, it focuses primarily on ensuring that only one of the two expectations listed above is adequately catered for – location.

While Australian voters do get a say in the political perspective of the politicians elected to our House of Representatives, it is secondary to location. This is because even though each electorate gets to vote for representatives from different political parties, the drawing of electoral boundaries between groups of voters – each of which only gets to elect a single representative – distorts the way seats are allocated to different political parties. (Want to know more? For an explanation on how physical electoral boundaries can change an election outcome, see Gerrymandering explained.)

How has this impacted the outcome of elections in Australia?

As previously mentioned, over the last thirty Federal Elections, Australia has ended up with an LNP government roughly two-thirds of the time despite voter preferences indicating a preference for the ALP 16 times to the LNP’s 14. That’s up to twelve more years of an LNP government than the people of Australia actually wanted plus another three on the way.

Further, if you take a more detailed look at some of the individual Federal Election results, there are other distortions. For example, in the 2013 Federal Election results, only 45% of Australians picked the LNP as their first preference for the House of Representatives, and yet the LNP ended up with 60% of the seats. Conversely, the Minor Parties and Independents received just over 21% of primary votes but ended up with only 3% of the seats.

What would a more accurate voting model look like?

A proportional electoral system is a voting model which factors in both location and political perspective. It typically does this by giving citizens two votes – one for an individual to represent their electorate and another for a political Party (or independent) that best represents their political views.

This type of voting system is used in 21 out of 28 democracies in Europe and is also used by our Kiwi neighbours. The great thing about this model is not only that it is able to more accurately reflect voters’ wishes, but according to former associate professor Klaas Woldring:

“The European model of proportional representation is co-operative, rather than adversarial in nature…Apart from being co-operative, it also ensures diverse and democratic representation. There are no byelections, pork-barrelling or horse trading on preferences behind closed doors.”

To give you some idea of how a proportional voting system works in practice – let’s take a quick look at the New Zeland model.

Proportional voting in New Zealand

In the New Zealand Mixed Member Proportional (or MPP) voting system, there are 120 seats in parliament – 71 of these are determined by whoever gets the most votes in each electorate (or location), and the balance are allocated proportionally according to the ‘share’ of the vote that a particular political party receives (as long as they receive a minimum of 5% of the vote across the country). Here’s a quick video which provides an overview of how New Zealand’s MPP works:

The New Zealand system is arguably more accurate than our current system because it factors in representing its citizen’s views both by location and by political perspective.

Would the outcome of the 2016 Australian Federal Election have been different if we used proportional voting?

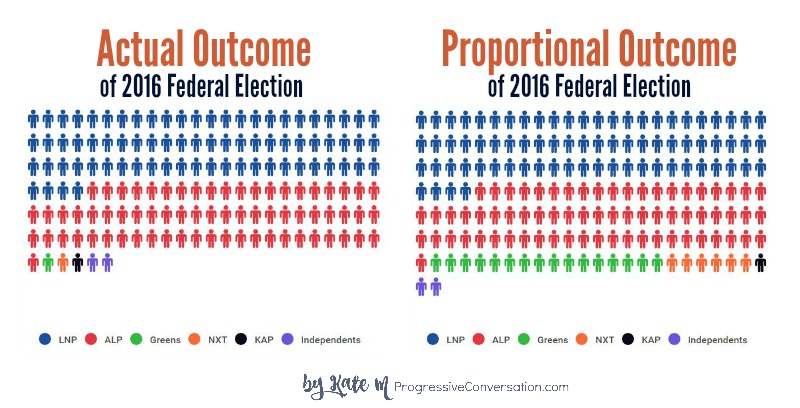

Very possibly – yes. Obviously, we don’t have that system in place, nor do we know exactly what a similar system would look like in Australia if deployed, so it’s impossible to tell for sure. However based on modeling I did use current AEC data and applying NZ rules for proportional allocation – I have looked at what the recent Election outcome might have been if Australia had added a ‘proportional’ component to determining who won seats in our House of Representatives. Here’s a visual representation of the difference between the actual outcome of the 2016 Federal Election, and what the House of Reps might have looked like if we had a proportional system in place:

- The big winners when you apply a proportional count would be:

- The Greens – who would have sixteen MPs in the House of Representatives (instead of one in our current model)

- The Nick Xenophon party – who would have six MPs in the House of Representatives (instead of one in our current model)

- All other elected representatives (under our current system) would keep their seats – including the two independent candidates (McGowan and Wilkie).

The bottom line: The ALP could be in government right now if we were using a similar model to the Kiwis

In the model above, neither the LNP nor the ALP have the 86 seats needed to form Government in their own right. However, in this scenario, assuming the ALP had entered into an arrangement with the Greens and Andrew Wilkie – even if only on supply and confidence motions – then they would have enough seats to form government. This suggests that had we used a proportional model in the 2016 Federal Election, the ALP could be in government now, and Bill Shorten would be Prime Minister.

What we do know

Any model can only ever be hypothetical. But what we do know about our current electoral system for the House of Representatives is that it is outdated and inaccurate. It’s so inaccurate in fact that it has arguably resulted in:

- Australia having 12 more years of an LNP government than we otherwise might have; and

- The ALP potentially missing out on an opportunity to take the reins of government in 2016 – despite having won the two-party preferred vote.

Turnbull promised in February this year to give us an electoral system that more accurately translates Australians’ votes into an election result. Clearly, we’ve still got a way to go.

(Note: there was an error in one of my numbers – picked up by an observant reader – Arthur, thank you. As a result, I updated them at 5:30 pm on 28 July to fix this error. Further – on 29 July the AEC issued updated numbers for the 2016 election which meant the AlP had won the two-party preferred vote in 2016, so I have updated the data to reflect this. The overall conclusions following both adjustments are the same.)

Assumptions used/notes regarding my modelFor those interested in the detail behind my model above, here are the assumptions I used and some additional notes:

|

Out of all seriousness I wonder if had ALP and the greens party hit home runs you probably wouldn’t have written this article. Don’t think I haven’t noticed the heavily biased journalism even if you try to make it as subtle as possible…you can’t get past me lol

LikeLike

The name of my site is ‘Progressive Conversation’. I don’t hide the fact that I lean left. It’s right there in the name. I discuss issues from a progressive perspective. That’s what I do.

Would I have written this if it had worked the other way? If the outcome of our electoral system had favoured the left instead of the right? Maybe. Maybe not. We will never know – it’s a hypothetical situation.

I don’t work for the ABC or any other news outlet – not do I work for or belong to a political party or anyone else actively involved in the political process. I’m an independent writer who decides what they want to look at and when they want to look at it. If something interests me I dig further and I write about it. Since I lean left, I’m obviously going to be interested in issues that concern the left more than the right. That’s why so many of my articles have been about the treatment of asylum seekers for example – which have not always been favourable about either party.

I certainly don’t recall dismissing an idea because it turned out in the LNP’s favour – but they are in government, so things are more likely to go against them. They are the ones doing the governing. It’s a lot harder to make mistakes from opposition because you aren’t the one driving the governmental car.

Regardless of my personal political perspective, if my arguments don’t hold up – if the facts don’t support the conclusions, then please say so. If you read my About this conversation section – you will see that again I say that I lean to the left, but that I want discussion to be about the facts, not left or right. So if you wish to challenge some of my conclusions on the basis of the facts – I would encourage you to do so.

Cheers.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh Jamie if you want to see “heavily biased journalism” read the Murdoch press. By the way, they charge you money to do so. Which is just one reason I don’t.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting article. For a long time now, I’ve wished we did adopt multi-member proportional representation. But the two major parties are highly unlikely to vote for it, one has to say.

Pedantic footnotes: (a) your “Proportional Outcome” graphic has 170 little people in it, not 169. (b) The ratio 19:11 isn’t, in my opinion, “nearly twice”. It’s 1.73. Why not say the LNP has formed government 73% more times than Labor? People can easily understand percentages, and they’re a whole lot more accurate than vague “almost twice as often” statements.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the heads up re numbers. Will take a closer look this evening.

LikeLike

Had a look at the numbers – and you were right – so I’ve updated them with a note 🙂 Thanks again for the headsup – much appreciated.

LikeLike

Pingback: Ever wondered why the Nationals have seven times as many seats as the Greens with less than half the votes? It’s all in the Gerrymander. | Progressive Conversation

This is a really shit article. Mixed Member Proportional is a terrible system because it assumes political parties as a basic unit of democracies, not individuals.

If PR must be used to elect the House, it should be Hare-Clark, a modified version of Single Transferable Vote, NOT the flawed MMP system!

LikeLike

Well quite frankly James, your comment is a ‘shit’ comment. The purpose of my article was to point out – to Australians – the flaws in our current model and to examine the model of our nearest neighbour (New Zealand), a model that many Australians have at least a passing level if familiarity with. Its goal was to show the impact a different model of voting can have on an election outcome and to highlight the flaws in our current outdated model. Your comment seems to inaccurately assume that my article was meant to be a comprehensive examination of all alternative models of government. It wasn’t. You could have added a constructive comment to the article suggesting the alternative models you mention. But instead you decided to be a little troll. If you are someone who knows something about this topic – and your comment suggests that you have at least a passing acquaintance with it – how about you consider adding constructively to this space in the future instead of being, well, a dick.

LikeLike

How about looking to our own country, not overseas? Tasmania’s lower house is proportional and uses the Australian designed Hare-Clark system.

We do not need inferior foreign systems here.

There are good arguments for more proportionality in the federal lower house but not at the cost of a terrible system like MMP.

LikeLike

I will just elaborate a bit more though, Kate. MMP systems see you voting explicitly for a party, as well as a local member. This enforces political parties as the basic unit of democracy, which is a total falsehood – people are.

A better system is Hare-Clark, where people vote, not for parties, but candidates, and rank them in order. This is basically equivalent to below the line voting in the Senate.

In Hare-Clark, there are generally multiple multi-member electorates, typically with about five people in them. This is so the list of candidates on the ballot sheet doesn’t get too incomprehensibly large. The names on the ballot sheet are grouped by political party, but the order is randomised, and how to vote sheets are banned near polling places. This means political parties don’t decide who gets elected, voters do. Party bosses can’t ensure their leaders are high up on a “party list” – every seat is competitive. This is the exact opposite of Mixed Member Proportional, which uses party lists, where party bosses, not voters, determine whether particularly candidates get elected.

More info here: http://www.prsa.org.au/hareclar.htm

Also, consider that Australia’s Senate already uses STV (which is close to Hare-Clark) to give a large measure of proportionality to our federal electoral system. There is some value in having stable majorities in the lower house. Also, the Nationals get more lower house seats not because of gerrymandering, but because their support is concentrated in geographical regions. It’s quite important that regional and rural people are represented, and party list proportional representation, including MMP, dilutes this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This comment is a bit necromantic, but on the other hand I’ve only just read this post.

I’d like to put in some support for MMP.

First off, in Australia, even in Hare-Clark-using Tasmania, party discipline is and was extremely strong. As such a candidate is only as good as their party (and of course, a party is only as good as their MPs).

Second, STV by its nature requires larger districts for an equivalent number of MPs. Rural districts are already large and the most remote ones (in outback Queensland for example) are almost unmanageably so. To make them any larger geographically would be farcical.

But to retain single-member districts for the outback regions while implementing multi-member districts for the coast would constitute a gerrymander of sorts favouring any party which does well enough to win the single-member outback districts. (Because those parties often wouldn’t win single-member-districts elsewhere, but would win 1 of 5 seats under STV.)

Third, there’s an extant variant of MMP, as used in Baden-Württemburg, where the order of additional MPs elected is determined by those MPs’ results in the district elections, not by the party bosses. There’s no reason we couldn’t use the same principle (although we of course would retain preferential voting for the districts, and could therefore rank candidates by their share of the vote after receiving any preferences, rather than by mere primary).

Fourth, it would also be quite straightforward to put in some regions (as clusters of districts) and then have the additional MPs for each party selected in such a way that there are MPs from each region (as much as possible).

Fifth, if you really care about proportionality, as I do, you’d recognise that STV is too coarse-grained to do it properly. Of course, so is MMP with a large threshold, but thresholds are pointless anyway.

Sixth, it’s entirely possible to have stable governments in a proportional system. The Dutch have managed it for a long time.

LikeLiked by 2 people