Poor little rich companies: No money for tax. Plenty for political donations.

While the government scrambles to look for ways to increase revenue and cut spending, one group of sacred cows who seem largely unperturbed by these ongoing discussions are Australia’s largest companies. That might be because around one in three of them pays no tax at all. And for those that do pay tax, there is talk of cutting the corporate tax rate in the future.

It seems that for this particular group of Australian tax payers, life is fairly rosie. And many of these companies are quick to show their gratitude to the crafters of Australia’s tax laws. In fact, many of those companies who cry poor when it comes to bearing their fair share of Australia’s tax burden, can still find the money to line the pockets of our nations’ political parties.

The poor little rich companies who donate to political parties

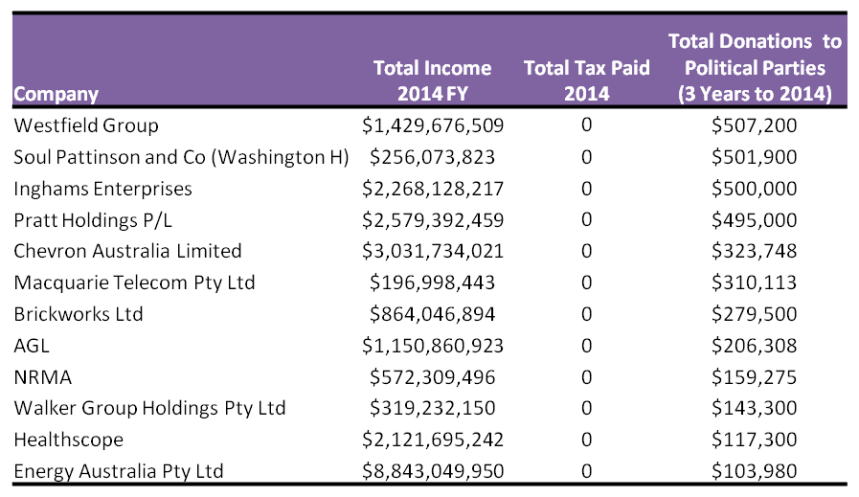

As has been reported in the last few months, over a third of Australia’s largest public companies and 30% of our largest private companies paid no tax at all in the 2013/14 tax year. When looking at the lists of these poor little rich companies, I noticed that they include a couple of large corporate political donors. So I decided to take a longer look at the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC)’s database of political donors for the last three years to see if I could identify any more poor little rich companies who, despite not earning enough taxable income to have to pay tax, were also large corporate political donors.

Bingo! Despite the fact that the AEC’s list of political donations is incomplete – thanks largely to John Howard’s changes to political reporting requirements in 2006 – it didn’t take long to identify over twenty large Australian companies who fit my search criteria. Here’s just some of the larger ones:

Other poor little rich companies worthy of an honourable mention include Macquarie Group Limited, who paid over 1.1 million to political parties over the last three years, and yet paid only 16% tax (instead of 30%) on their income for the 2014 tax year – and Santos (an oil and gas company) who paid over $600,000 to political parties and paid just under 15% tax during the same periods.

If all these companies have been able to establish for the ATO that they should pay little or no tax in the 2014 tax year, how is it that they can justify donating substantial sums to one or more of our political parties over the last three years?

Why do companies donate to political parties?

The answer to this is not going to shock you. The reason companies donate to political parties is not altruism or to be good corporate citizens – it’s purely and simply to gain financial advantage.

In fact, ‘profit maximisation’ is the only legal reason a public company can donate to a political party in Australia, and they aren’t afraid to admit it. In a High Court case heard in late 2015 that centered around reforms to NSW political donations, a key part of property developer Jeff McCloy’s legal case as to why property developers should be able to donate to political parties was that it enabled them to:

.…gain access to politicians, acquire influence and advance the interests of businesses.

(MsCloy v NSW, 2015)

Clive Palmer: a new breed of corporate political donor

There has arguably never been a more blatant example of a company using political donations to buy its way into achieving its corporate goals than mining magnate Clive Palmer and his Palmer United Party (PUP). Palmer’s mining companies donated millions of dollars to ensure that he – and other representatives of PUP – were elected in the 2013 Federal Election following an extensive advertising blitz.

On Palmer’s website for the 2013 election, he had only five policies – three broad policies about things like security, and two very specific policies:

- “Abolish the carbon tax” – a tax which had hit his companies hard; and

- “Create mining wealth” – Palmer really couldn’t have been more specific about wanting to use his political clout to advance his companies.

We all know the outcome of the 2013 election – Palmer was voted into the House of Representatives and three of the PUP party candidates were voted into the Senate. And whilst Palmer himself has little influence in the House of Representatives, his three Senators held the balance of power in the Senate – at least initially. On taking office, one of their first priorities in the Senate was to use their power to pass legislation abolishing the carbon tax and the mining tax.

‘Check’ and ‘check’ to PUP’s two specific political goals – a win for Palmer’s companies and other mining and resource companies. But as I wrote last year abolishing the mining and carbon taxes was a major loss for the Australian public who:

- lost two major sources of revenue,

- saw few if any new jobs created as a result of the taxes being cut, and

- had a successful carbon reduction program replaced with one that actually increased carbon emissions and cost a lot more money.

Palmer came under criticism for the extensive money he took out of his mining companies for his election campaign when his Queensland Nickel plant went into receivership in 2015. At that time, the $15 million dollar donation Queensland Nickel had made to the PUP campaign in 2013 came into question. According to Palmer, that $15 million political donation could not have been better spent:

“That [donation] saved the refinery $24 million a year.”

(Clive Palmer, January 2016)

Palmer has arguably taken corporate influence in politics to a new level by funding his own political party and literally buying votes in parliament through his campaign’s successful advertising spend. (Of course that backfired on him when two of his Senators quit the party, but by that stage he had already achieved two of his goals.) And while Palmer is arguably unlikely to continue in parliament for any length of time – most likely because he won’t be voted in again – if his key aims were abolishing the carbon and mining taxes, he doesn’t really need to.

You have to wonder whether Palmer’s foray into politics is a strategy that other companies or even industry bodies may replicate. And while they may not end up as lucky as Palmer was to hold the balance of power in one of our houses of parliament, they may still have significant influence.

Which bring us back to….

The Politicians’ Precious: Large political donations

Image from abbotfail.com

There’s no doubt that having money to invest in advertising is important to a political party being elected. And it’s for this reason that political parties value corporate donors. An analysis of political donation by type on the Green party’s Democracyforsale website shows that around 75% of donations to political parties (where the source can be identified) come from companies. When you factor in money that companies give to politicians through tickets to fund-raising events and forums – which doesn’t have to be declared to the AEC – the percentage of support that political parties receive from companies may be even higher.

And those donations, as noted above, often come with access to politicians and therefore potentially the ability to influence the political process.

Many politicians – like our own Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull – profess to believe in reforming political donations until they are in charge of the political donations honeypot. Then, like Gollum holding onto his precious ring, they don’t want to give up the precious corporate donors that they believe help them to stay in power – and they become very quiet on the matter. Suddenly the problem of corporate donations doesn’t seem quite so pressing to them…

But it is. Dealing with the influence of large political donations has been urgent for a while.

If you do a search on political donations, you’ll see article after article highlighting the pitfalls of large donations to political parties – whether from corporates or individuals. You’ll find academics, businessmen, justices, even politicians who have been calling for reform on this front for decades. There was even a parliamentary inquiry in 2011 into political donations which recommended changes – particularly to disclosure requirements. But still nothing has happened.

Here’s just some of the voices who have called for reform:

The Old Malcolm Turnbull (circa 2005)

High Court Justices

“guaranteeing the ability of a few to make large political donations in order to secure access to those in power would seem to be antithetical to the great underlying principle [of the equitable distribution of power in a democracy]”

(McCloy v New South Wales: French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Keane JJ, 2015)

The ANU’s Democratic Audit of Australia

“There is inadequate transparency of funding. Moreover, there is a grave risk of corruption as undue influence due to corporate contributions and the sale of political access” (Sally Young and Joo-Cheong Tam, 2006)

Chairman of the Australian Shareholder’s Association

John Hewson (former leader of the LNP):

For now, the poor little rich companies keep on giving….

Clearly there is a no shortage of calls for the reform of political donations, and equally clearly, the reform of political donation laws is no simple matter – but that doesn’t mean it can’t be done. In Canada, corporations and unions are banned from making donations to political parties and individual donations are capped at $1500 per annum. Some say this is extreme – I say it sounds reasonable. At the very least, it would stop our poor little rich companies from having to keep on giving. And you never know – it might even result in laws which require them to actually pay tax instead.